With Cultural Integration, 'People Will Always Need to Create Others'

Eden Collinsworth

Eden Collinsworth is a former media executive and business consultant. She was president of Arbor House Publishing Co. and founder of the Los Angeles monthly lifestyle magazine Buzz before becoming a vice president at Hearst Corp...

The following book excerpt is from “Behaving Badly: The New Morality in Politics, Sex and Business,” by Eden Collinsworth, published by Doubleday/Nan A. Talese in 2017.

Edie Weiner is acknowledged in the United States as one of the most influential practitioners of social, technological, and political trend spotting. I have flown from London to New York to ask her whether there are correlations between morality and ethics, and the law and justice.

Ms. Weiner first wants to make sure I understand what I’ve managed to conclude on my own: that morality differs from ethics, but that neither is the same thing as justice. “And there’s no guarantee justice and the law are the same,” she warns.

I ask Ms. Weiner if she thinks human nature—greed, in particular—instigates our attempts to outwit the law.

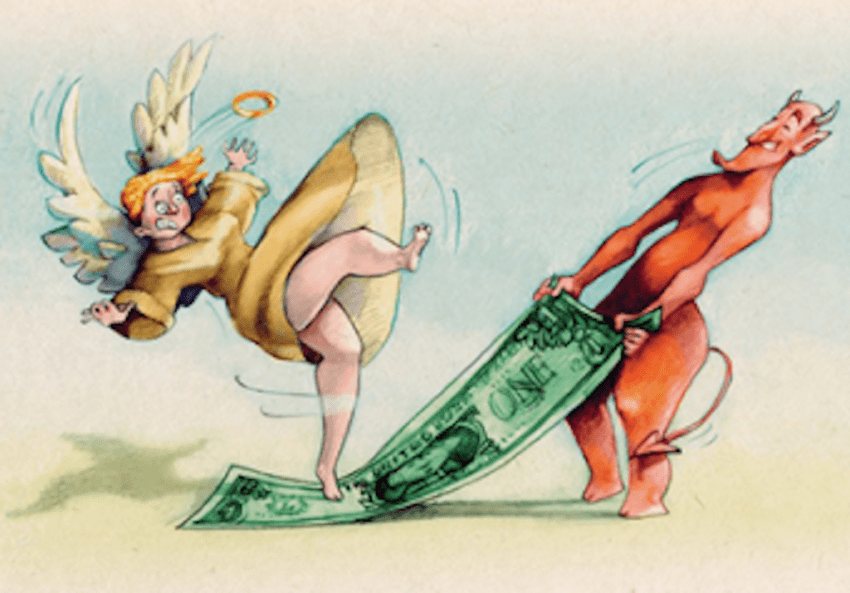

“It’s many people’s human nature to do precisely that, and many people’s not to,” she says. “Selfishness cannot be kept in check without altruism, and humankind can’t progress without the two: selfishness and altruism. It’s only when the two are in balance that we get ahead.”

“And morality?”

“Morality is what you’re answerable to within yourself, whatever that higher order is . . . something exercised by an individual that says to him or her, ‘Even though this is not against the law, I shouldn’t do this.’ ”

“What about ethics?”

“Ethics exist in order to bind together people in a given society by providing behavioral consistency and solidarity. Ethics have penalties attached if you don’t abide by them. Ethics are situational. They’re opportunistic. They’re politically based and are dictated by people with power in a particular arena. It could be business. It could be the law. It could be the military.”

I tell Ms. Weiner that from what I’ve seen in my travels, ethics are almost entirely relative to place. China performs executions on a regular basis; America does so now and again, depending on state-by-state legal variants. Most countries in Europe never do. The Middle East is a veritable execution bazaar. Are Europeans the most moral? I want to know, but instead ask Ms. Weiner if she thinks there’s validity in moral absolutes.

“People have a societal take on moral absolutes,” she tells me. “I think that’s why people in America who can afford it are moving into communities that are like-minded. Unfortunately, those like-minded communities are breeding future generations of people who believe as they do, as opposed to a broader-thinking society of mixed races and religions. It’s what’s pulling us apart.”

An idealist who grew up in the 1970s, at one time Ms. Weiner embraced the belief that separate cultures in a shared, diverse society should merit equal respect and an equal say. Now she wonders whether, in its rush to accommodate multiculturalism, America’s ideology has led to its institutional and political failure.

To many, this might be construed as an un-American way of thinking; after all, the pursuit of happiness is a cornerstone of America’s Declaration of Independence. But while it’s true that no other country but America has evolved so many different ways for citizens to remain individuals, it’s also true that its conflicting values have created a polarized climate. I ask Ms. Weiner how, in a nation’s racial and cultural mishmash, she proposes we reframe moral issues.

“You leave the word ‘morality’ out, and you bring in the word ‘culture,’ ” she tells me.

I remark that globalization has shrunk physical distance, but the same cannot be said about cultural chasms. Ours is an era of churn, with more displaced people than ever before, many fleeing to countries with very different moralities. Do we force cultural and moral integration in order for everyone to become more like us?

Ms. Weiner lingers in frowning concentration, and when she answers, it is in a roundabout way, but one that is also clear.

“I grew up in foster homes among people with the same religion, in the same community, in the same era. Still, each time I changed families, I was instructed to adhere to a different absolute way to do things, to act, to think. What we come to believe is absolute is nothing more than the reality in our minds.”

She remarks that America is a nation that takes from every culture in the world and builds on an incredibly wide range of moralities.

“We have more people from other countries than some of the host countries they come from. America has been absorbing this type of universality since the time it was born,” she tells me, before suggesting that America might have an advantage over other countries when it comes to the thorny issues today of assimilating an unrelenting flow of immigrants and refugees.

“If you take a look at the Netherlands, for example—always praised for being so liberal and open—what do you think is happening there, with almost one million Muslims?”

I’m not sure what is actually happening in the Netherlands, but from Ms. Weiner’s condemnatory tone, I assume it involves backpedaling.

“Behaving Badly: The New Morality in Politics, Sex and Business”

Click here to see long excerpts from “Behaving Badly” at Google Books.

She tells me that, when the number of Muslims shifted upward there, a white supremacy movement emerged. “In the Netherlands,” she repeats, shaking her head. “Of all places.”

We sit in momentary silence, and then a wan smile creeps across her face. Hers is a world-weary sense of humor when she tells me that the solution to those who seem to be open-minded is to allow a few into their club; it’s never to join the other club.

“As long as the numbers don’t swing to the other side, everyone can feel morally wonderful.”

She points out that Muslims are procreating at a rate of ten to one in the developed world, making demographic change in other countries inevitable because, at the same time, the native born are aging. We fall into agreement that what will eventually counter the current generation’s insular instincts are their children. Young people will continue to flock to vibrant cities for employment, and they will have a very different take from their parents on issues that come with a mixed demographic.

“But what happens until then? What about now?” I ask.

Ms. Weiner tells me that people should not be forced to relinquish their cultural identity when they immigrate but that a more effective approach to cultural integration is required than currently exists. She tells me that there are two important things to understand about a culture: its rewards and its punishments. America—a nation whose founding principles recognized the individual—has not forsaken the individual, but it has become less concerned with that individual’s background, his or her beliefs, and what he or she learned at home or in church.

“In effect, our country’s policies and laws are beginning to say that if you want to belong, these are the rules. We don’t care about your Confederate flag, your religious beliefs, your sexual beliefs—these are the rules of this cultural society. Get used to it.”

Staring intensely at the floor, she looks up with an expression that tugs at sadness.

“That won’t rid us of prejudice,” she tells me. “People will always need to create others.”

Leaving Ms. Weiner’s office during Manhattan’s rush hour, I join a dense herd of humanity trying to get home. As I head toward the bus stop down the block, a shrill sound of angry horns is directed at a man holding up traffic by double-parking his truck. A cabdriver, stuck directly behind the truck, has gotten out of his cab, presumably to take his complaint directly to the source of the problem. The two men begin to shout at each other: not an unusual method of expression on New York City streets. As an on-and-off New Yorker, I, too, have, on occasion, handled my own skirmishes there with a variety of unattractive words, but what the truck driver yells at the dark-skinned cabdriver shocks me to the core.

“Get out of my country!” is what I hear for the first time in a city where virtually everyone has come from some other place.

Wedged in a crowded express bus inching downtown, I mull over how the truck driver might have convinced himself that America belongs to only his kind, whatever he perceives his kind to be. I wonder if he is aware that whites have dropped below half of all Americans under the age of five. He might even know—but is too angry or afraid to admit—that, despite the promises made to him by politicians, nothing can prevent the modern world’s unrelenting mass mobility, and that it is the combination of others that will imagine our future.